|

Good and bad business communication examples can serve as effective teaching aids. The hard part is finding the examples. Search no more. In my teaching, I love to teach a principle and then show illustrating examples in authentic documents. The problem is that authentic examples are hard to come by. To help remedy this issue, I created the list below to serve as a link repository where business communication and technical communication instructors can find examples. To keep things simple, I’m keeping the detail in the list short and to the point. If you need to find a specific genre, audience, format, or industry, consider using CTRL-F (or CMD-F) and to search this page for the keyword you’re interested in. Remember that what constitutes effective or ineffective communication hinges upon many factors, including the criteria set forth in the textbook you’re using. Therefore, I recommend determining your criteria for what good and bad examples will look like before you begin searching for examples. This practice should save you some time and ensure that the examples you find reflect the principles you’re illustrating to your students. I’ll continue to update the table with other examples that I find. I welcome your comments below with any other examples to add to the collection. I hope you’ll find it useful. Also, if you or your students need a great resource for document conventions, take a look at the free business document formatting guide available on our site. --Matt Baker AnnualReports.com From the site: “Search 111,928 annual reports from 9,179 global companies.” Tips: The search bar is right on the home page. You can search by company name or ticker symbol. Bplans.com From the site: “Browse our library of over 500 business plan examples to kickstart your own plan.” Tips: These plans are not authentic business plans, but they provide numerous examples across many industries, so I think they’re worth including here. To find the plans, click on the “Sample Plans” link located at the top of the page and then browse for a plan of interest by industry. Grants.gov From the site: The site’s mission is to “provide a common website for federal agencies to post discretionary funding opportunities and for grantees to find and apply to them.” In essence, the site houses grant opportunities from the U.S. government. Tips: Use the search field in the top right-hand corner of the site to search for grants including the keyword of your choice. On the results page, select the link in the “Opportunity Number” column for your grant of choice. You’ll see a synopsis of the grant, but you can click on the “Related Documents” tabs to find links to the entire grant. Library of Congress From the site: “The Library of Congress is the largest library in the world, with millions of books, recordings, photographs, newspapers, maps and manuscripts in its collections. The Library is the main research arm of the U.S. Congress and the home of the U.S. Copyright Office.” Tips: You’ll see a search bar at the top of the page. If you’re looking for a specific document type, such as memos, letters, or emails, type it in the field. On the results page, you can then filter based on the type of data you’d like to see, such as PDFs. You can find some interesting things here, such as the Enron email dataset or historical NEH grants. (I tried downloading the Enron email dataset, and please be aware that it’s an enormous file.) NASA Technical Reports Server From the site: “Conference papers, journal articles, meeting papers, patents, research reports, images, movies, and technical videos – scientific and technical information (STI) created or funded by NASA.” Tips: Use the search bar at the top to find resources. The search results page includes additional search filters. Once you find a document you want to download, click the download icon in the bottom right-hand corner of the search result. Also know that because this is government-generated content, it’s in the public domain. Sam.gov From the site: “Anyone interested in doing business with the government can use this system to search opportunities.” In essence, whereas Grants.gov focuses on listing grant opportunities, Sam.gov lists requests for proposals (RFPs) for companies seeking to complete contract work for the U.S. government. Tips: Click on the “Search” tab located in the middle of the screen. In the search field, click on a keyword of interest. In the results, click on the title of a contract opportunity that interests you. The detail of the opportunity with then be displayed in your web browser, but please note that statements of work (SOW), requests for quotes (RFQ), and other documents can be downloaded in PDF format at the bottom of the web page. Ted.com From the site: “TED is a nonprofit devoted to spreading ideas, usually in the form of short, powerful talks (18 minutes or less).” Tips: Click on the “Watch” menu to search for talks. Advanced search options are available. TheWhitePaperGuy.com From the site: “I'm a seasoned white paper writer who’s done hundreds of B2B content projects.” Tips: Click on the menu and find the “Samples” area. You’ll find numerous examples of white papers in PDF format. UCSF Industry Documents Library From the site: “The Industry Documents Library is a digital archive of documents created by industries which influence public health, hosted by the University of California, San Francisco Library. Originally established in 2002 to house the millions of documents publicly disclosed in litigation against the tobacco industry in the 1990s, the Library has expanded to include documents from the drug, chemical, food, and fossil fuel industries to preserve open access to this information and to support research on the commercial determinants of public health.” Tips: The search bar at the top includes an advanced search option. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics From the site: “The Bureau of Labor Statistics measures labor market activity, working conditions, price changes, and productivity in the U.S. economy to support public and private decision making. . . . The first BLS Commissioner, Carroll D. Wright, described the Bureau’s mandate as ‘the fearless publication of the facts.’” Tips: To begin your search, click on the Publications link at the top of the page. In In my teaching, Know that part of the site is dedicated specifically to teachers as well. In my teaching, I’ve used this site primarily for data displays.Because this is government-generated content, it’s in the public domain. U.S. Government Accountability Office From the site: “GAO provides Congress, the heads of executive agencies, and the public with timely, fact-based, non-partisan information that can be used to improve government and save taxpayers billions of dollars.” Tips: To get started in your search, click on View Topics at the top of the site. Also know that because this is government-generated content, it’s in the public domain. In my teaching, I’ve used this site mostly for example reports, but it also includes other genres such as blog posts and videos.

0 Comments

In one of our previous posts, we reviewed research about a way to assess whether students are considering their audience as they write; in this post, we review research about how students can enhance their consideration of their audience in their writing.

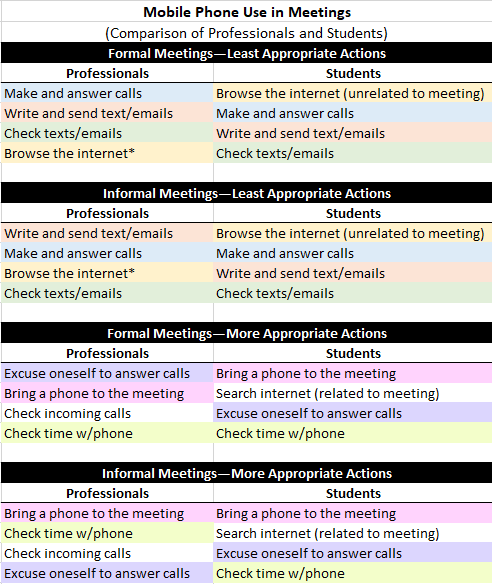

The Research This research is less recent than some of the studies we reviewed in other posts, but its conclusions are worth highlighting. Linda Carey, Linda Flower, John R. Hayes, Karen A. Scrivener, and Kristina Haas from Carnegie Mellon investigated how planning can affect writing quality. The researchers assigned a writing task to 7 novice writers and 5 expert writers. All 13 writers were to write to the same audience. As the writers completed their writing task, they were asked to speak their thoughts out loud so the researchers could capture their thought processes. Any thought processes that occurred before the writers wrote their first complete sentence were considered statements related to planning. The researchers analyzed the planning statements for content, for persuasion (purpose, audience, and organization), and for other goals. After the writers composed their documents, the quality of the documents were evaluated for audience adaptation, clarity of purpose, and structure. The results indicated that writers who planned for all three persuasive elements—purpose, audience, and organization—produced higher-quality documents. Further, writers of high-quality documents tended to plan more overall. Notably, these results transcended expertise, as three novice writers and three expert writers achieved the highest quality scores. The Implications The results indicate that if we can help our students plan more for purpose, audience, and organization, their writing will likely reflect greater attention to those persuasive elements. And in my experience, greater attention to those elements translates to higher-quality writing. To help my students plan for persuasive elements, I encourage them to analyze these elements using the PACS framework. In addition, when they organize information, I encourage them to not only categorize the information but also sequence the information so it meets the audience’s needs and is sensitive to the purpose of the document. Finally, I use case studies to build a rich situation so students have a purpose and audience to respond to. What strategies do you use to help your students plan for persuasive elements? We’d love to hear about them in the comments below. –Matt Baker Source: Center for the Study of Writing Image by DarkmoonArt Today’s ubiquitous mobile phones are used for getting directions, listening to music, watching movies, accessing the internet, sharing on social media, taking photographs, managing calendars, playing games, conducting business, shopping online, and more. The features and benefits of mobile phones are unarguably impressive, but some mobile-phone usage is disruptive to other activities, such as conducting meetings. The Research A recent research article, “Not So Different? Student and Professional Perceptions of Mobile Phone Etiquette in Meetings,” reported research about students’ perceptions of mobile-phone usage in meetings. The objective of the study, by Emil B. Towner, St. Cloud State University; Heidi L. Everett, Minnesota State University Moorhead; and Bruce R. Klemz, St. Cloud State University, was (1) to analyze student perceptions of appropriate mobile phone behavior in formal and informal meetings and (2) to compare the student perceptions with those of working professionals as revealed in a previous study. The anonymous online survey was conducted at a medium-size Midwestern university. In additional to including questions about mobile phones usage in formal and informal meetings, the survey included questions related to gender, age, education, and major. The following table shows a high degree of agreement regarding what professionals and students think about mobile phone usage in meetings. The color coding reveals only minor variations in the rankings. *The original study of professionals did not distinguish between browsing the internet and searching the internet for answers to questions relevant to the meeting.

Probing into variances in student demographics, the data analysis also revealed a slight movement of perception between students’ freshman and senior years, with younger students being more accepting of mobile phone usage in meetings and more mature students being less accepting of checking texts/emails during informal meetings. Additional findings also revealed that females are more likely to use mobile phones in their daily routines but are less likely to view mobile-phone usage in meetings as being appropriate. The Implications Overall, this study showed a high degree of correlation between students’ and professionals’ perceptions about appropriate and inappropriate use of mobile phones in formal and informal meetings. Thus, there does not appear to be a great need to spend significant classroom time teaching mobile phone etiquette in meetings. However, instructors would certainly be justified in taking time to briefly review the most- and least-acceptable mobile-phone behaviors in meetings as identified in this study. You can read the entire article here. Also feel free to share your own thoughts and insights in the comments. How do you teach your students about using mobile phones? How do you control mobile phone usage in your classroom? To learn more, check out Chapter 1 in our textbook on controlling mobile phones in meetings. -Bill Baker Source: Business and Professional Communication Quarterly Image by Headway Business communication instructors agree that audience is a key consideration when composing business documents. But how do we know whether students are grasping what we're teaching them about the importance of audience? Reflections can be a good choice.

The Research In new research, Danica Schieber from Sam Houston State University and Vincent D. Robles from the University of North Texas assessed the use of reflections to gauge their students' awareness of audience. After responding to a case requiring them to write multiple business genres to varying audiences, students reflected on their audience awareness. The researchers uncovered three themes in the students reflections: -Identifying reader benefits and constraints -Considering reader values and priorities -Estimating one's own credibility The researchers found that students faced most difficulty delivering bad news to a customer and persuading a manager. Students found it difficult to "keep a positive tone while still giving bad news." When persuading a manager, students found it difficult to sound and feel credible, to avoid sounding "bossy," and to provide adequate detail. The Implications This study suggests that reflections can be a great tool for instructors to gauge their students' awareness of audience. Further, it suggests that different combinations of audiences (e.g, a customer versus a manager) and genres (e.g., persuasive versus bad news) can increase the difficulty of audience-focused assignments. If instructors want to provide their students with increasingly challenging practice, they might systematically adjust assignment audiences from an external customer to colleagues to a manager and adjust assignment genres from an informative message to a bad news message to a persuasive message. For additional information that can help students strategically consider their audience, consider using our PACS framework described in this post or in Chapter 2 of our textbook. You can also read the entire article “Using Reflections to Gauge Audience Awareness In Business and Professional Communication Courses” by Danica Schieber and Vincent D. Robles to learn more about using reflections to assess your students’ awareness of audience. If you have assignments or teaching strategies you use to help your students gain an awareness of audience, please share them in the comments below. -Matt Baker Source: Business and Professional Communication Quarterly Image by Free-Photos In your business communication courses, do you ever wonder how much emphasis you should be placing on writing emails? In “The Snowball of Emails We Deal With’: CCing in Multinational Companies,” Ifigeneia Machili of University of Macedonia, Greece; Jo Angouri of Warwick University, UK; and Nigel Harwood of University of Sheffield, UK confirm that email is the current most dominant business communication genre.

Emails are not, however, alone on center stage. They interweave with video conferences, phone calls, texts, webinars, and more. Also, they function interdependently with previous and subsequent emails, reports, face-to-face conversations, social media, local and remote meetings, and phone calls. Further, emails must be fluid and flexible as they develop credibility, build/maintain social and organizational relationships, and be sensitive to formality, politeness, credibility, accountability, self-projection, and multiple audiences. The Research In their analysis of email chains in an international organization, the researchers found that emails play a pivotal role in managing interpersonal relations and operational matters. Through discourse-based interviews, the researchers learned how employees strategically highlighted their professional achievements and owned or denied responsibility for decisions throughout the email chains. In addition to transmitting information, emails employed CCing (carbon copying) and formality to help (1) establish accountability, (2) contribute to decision-making, and (3) enable self-projection. The Implications The results validate the need for business communication instructors to include intensive email instruction. Students must realize that emails are not simple one-and-done messages, but rather critical communication exchanges that must be sensitive to a host of subtle contextual factors. Showing real-world email chains can help students become aware of the contextual twists and turns they will encounter on the job. Using scenarios and simulations, instructors can require students to write emails at different points in an email chain, developing appropriate strategy and content and deciding whom to CC. You can read their entire article here. Learn other tips about creating effective emails in Chapter 3 of our textbook Writing and Speaking for Business. -Bill Baker Source: Business and Professional Communication Quarterly Image by William Iven |

AuthorsWe're Bill, Matt, and Vince, and we hope these posts will help you more effectively teach business and professional communication. If you like what you read, please consider teaching from our business and professional communication textbook. Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed