|

Good and bad business communication examples can serve as effective teaching aids. The hard part is finding the examples. Search no more. In my teaching, I love to teach a principle and then show illustrating examples in authentic documents. The problem is that authentic examples are hard to come by. To help remedy this issue, I created the list below to serve as a link repository where business communication and technical communication instructors can find examples. To keep things simple, I’m keeping the detail in the list short and to the point. If you need to find a specific genre, audience, format, or industry, consider using CTRL-F (or CMD-F) and to search this page for the keyword you’re interested in. Remember that what constitutes effective or ineffective communication hinges upon many factors, including the criteria set forth in the textbook you’re using. Therefore, I recommend determining your criteria for what good and bad examples will look like before you begin searching for examples. This practice should save you some time and ensure that the examples you find reflect the principles you’re illustrating to your students. I’ll continue to update the table with other examples that I find. I welcome your comments below with any other examples to add to the collection. I hope you’ll find it useful. Also, if you or your students need a great resource for document conventions, take a look at the free business document formatting guide available on our site. --Matt Baker AnnualReports.com From the site: “Search 111,928 annual reports from 9,179 global companies.” Tips: The search bar is right on the home page. You can search by company name or ticker symbol. Bplans.com From the site: “Browse our library of over 500 business plan examples to kickstart your own plan.” Tips: These plans are not authentic business plans, but they provide numerous examples across many industries, so I think they’re worth including here. To find the plans, click on the “Sample Plans” link located at the top of the page and then browse for a plan of interest by industry. Grants.gov From the site: The site’s mission is to “provide a common website for federal agencies to post discretionary funding opportunities and for grantees to find and apply to them.” In essence, the site houses grant opportunities from the U.S. government. Tips: Use the search field in the top right-hand corner of the site to search for grants including the keyword of your choice. On the results page, select the link in the “Opportunity Number” column for your grant of choice. You’ll see a synopsis of the grant, but you can click on the “Related Documents” tabs to find links to the entire grant. Library of Congress From the site: “The Library of Congress is the largest library in the world, with millions of books, recordings, photographs, newspapers, maps and manuscripts in its collections. The Library is the main research arm of the U.S. Congress and the home of the U.S. Copyright Office.” Tips: You’ll see a search bar at the top of the page. If you’re looking for a specific document type, such as memos, letters, or emails, type it in the field. On the results page, you can then filter based on the type of data you’d like to see, such as PDFs. You can find some interesting things here, such as the Enron email dataset or historical NEH grants. (I tried downloading the Enron email dataset, and please be aware that it’s an enormous file.) NASA Technical Reports Server From the site: “Conference papers, journal articles, meeting papers, patents, research reports, images, movies, and technical videos – scientific and technical information (STI) created or funded by NASA.” Tips: Use the search bar at the top to find resources. The search results page includes additional search filters. Once you find a document you want to download, click the download icon in the bottom right-hand corner of the search result. Also know that because this is government-generated content, it’s in the public domain. Sam.gov From the site: “Anyone interested in doing business with the government can use this system to search opportunities.” In essence, whereas Grants.gov focuses on listing grant opportunities, Sam.gov lists requests for proposals (RFPs) for companies seeking to complete contract work for the U.S. government. Tips: Click on the “Search” tab located in the middle of the screen. In the search field, click on a keyword of interest. In the results, click on the title of a contract opportunity that interests you. The detail of the opportunity with then be displayed in your web browser, but please note that statements of work (SOW), requests for quotes (RFQ), and other documents can be downloaded in PDF format at the bottom of the web page. Ted.com From the site: “TED is a nonprofit devoted to spreading ideas, usually in the form of short, powerful talks (18 minutes or less).” Tips: Click on the “Watch” menu to search for talks. Advanced search options are available. TheWhitePaperGuy.com From the site: “I'm a seasoned white paper writer who’s done hundreds of B2B content projects.” Tips: Click on the menu and find the “Samples” area. You’ll find numerous examples of white papers in PDF format. UCSF Industry Documents Library From the site: “The Industry Documents Library is a digital archive of documents created by industries which influence public health, hosted by the University of California, San Francisco Library. Originally established in 2002 to house the millions of documents publicly disclosed in litigation against the tobacco industry in the 1990s, the Library has expanded to include documents from the drug, chemical, food, and fossil fuel industries to preserve open access to this information and to support research on the commercial determinants of public health.” Tips: The search bar at the top includes an advanced search option. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics From the site: “The Bureau of Labor Statistics measures labor market activity, working conditions, price changes, and productivity in the U.S. economy to support public and private decision making. . . . The first BLS Commissioner, Carroll D. Wright, described the Bureau’s mandate as ‘the fearless publication of the facts.’” Tips: To begin your search, click on the Publications link at the top of the page. In In my teaching, Know that part of the site is dedicated specifically to teachers as well. In my teaching, I’ve used this site primarily for data displays.Because this is government-generated content, it’s in the public domain. U.S. Government Accountability Office From the site: “GAO provides Congress, the heads of executive agencies, and the public with timely, fact-based, non-partisan information that can be used to improve government and save taxpayers billions of dollars.” Tips: To get started in your search, click on View Topics at the top of the site. Also know that because this is government-generated content, it’s in the public domain. In my teaching, I’ve used this site mostly for example reports, but it also includes other genres such as blog posts and videos.

0 Comments

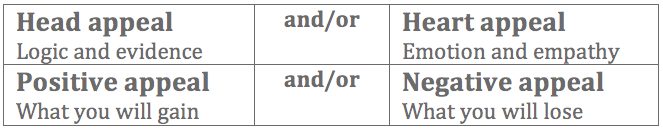

The recent solar eclipse prompted me to do a bit of symbolic thinking about smaller, less important things getting in the way of larger, more important things. In the early days of my teaching business presentations, my mentors stressed the importance of watching out for little presentation details, such as using the hands for precise gesturing or counting the number of times each presenter said “um” or “ya know.” Therefore, I emphasized these matters in my classes, and my students would then concentrate on using more gestures and controlling their normal speech patterns as they gave their presentations. Unfortunately, the students’ gestures were often awkward and unnatural—suggesting that even more emphasis was needed. It was a vicious cycle. Finally, after a few years, I realized that I may have been doing more harm than good in giving feedback of this type. I concluded that if my students were concentrating on these secondary matters while giving their presentations, they were thinking about the wrong things. The hand gestures and filler words were eclipsing the more important message and audience issues that should have been their primary focus. So what should we be thinking about as we present? First, we should constantly think about the purpose of our presentation—what we are trying to achieve by giving the presentation. This can be brought into sharp focus with an action statement like, “As a result of my presentation, I want the audience to . . .” This might include what we want them to understand, or feel, or do. Every informative and persuasive element should align with the central purpose of the message. Each element should move the audience from where they were when we started the presentation to where we want them to be when the presentation ends. Further, nothing should either distract or detract from that purpose. Second, we should think about connecting with the audience. If we have performed a careful audience and context analysis during the planning phase, we’ll understand the audience demographics and psychographics. We’ll know of their challenges and concerns. We’ll know what parts of our presentation will be readily accepted and which ones might not. And we’ll continuously focus on building and strengthening the audience members’ connection with us and with the content we are presenting. Third, we should constantly analyze the audience feedback as we present. Because most of this feedback comes in nonverbal form, we should assess the audience energy level, receptivity level, eye contact, facial expressions, and general responsiveness. We should then take impromptu corrective action when audience feedback tells us that the message isn’t getting across as well as it should. Finally, we should remain aware of the element of time, making sure we pace our presentation so we don’t speak too long. As appropriate, we should omit some of the less important planned information, without negatively affecting overall message clarity, impact, or coherence. Less-important content should never push aside more important content. So what about the “ums,” the “ya knows,” and the awkward gestures that I once thought were so important to teach? My experience has taught me that as students prepare content they are excited about, rehearse thoroughly so they are comfortable with the subject matter, and focus on connecting with the audience, these language and gesture issues mostly take care of themselves. The appropriate voice energy and gestures occur automatically. Better yet, they are normal and natural, not forced and awkward. With this change of focus, the less-important secondary elements of presenting no longer eclipse that which is most important—the message and the audience! -Bill Baker Most of our blogs have focused on topics related to business writing, but with the presidential debates occupying so much of our news these days, it seems appropriate to address a few factors related to oral persuasion. As the pundits argue about who won the first presidential debate, remember that the most important point is not who won that debate, but rather who will win the election in November. The first debate was simply one step along the way. Nevertheless, the outcome of future debates, and the entire election, might hang on the principles described in this month’s blog. A number of forces are at work when you attempt to persuade an audience. Graber (2003, 182) has identified four factors that affect your ability to persuade and influence others: 1. You must have relevant information. 2. You must have social capital (respect and credibility). 3. You must have good persuasion skills. 4. The audience must be open to persuasion. Let’s examine Graber’s four persuasion factors as they relate to the message, the messenger, and the audience. Message The message element addresses the first of Graber’s factors—the need to have relevant information. To select relevant information, take time to complete a thorough PACS planning process. Identify the purpose(s) of your presentation, analyze your audience, analyze the context in which you’ll be presenting, and develop a strategy. (Follow this link for more information about PACS: https://goo.gl/Hdsyfl.) When you are persuading, your relevant information should strengthen your own position and weaken the position of your opposition. Also, because humans are thinking and feeling creatures, your relevant information should include both logical arguments (Aristotle’s concept of logos) and emotional arguments (Aristotle’s concept of pathos). The relevant information you choose to share may also be either positively or negatively oriented, appealing to what the audience will gain by accepting your proposal or what they will lose if they don’t. People respond to both gain and pain appeals, those that help them achieve worthwhile gain or ease their pain. You may focus on a variety of pains and gains, including financial, emotional, political, physical, and more. Regarding pain appeals, however, there’s a big difference between a mosquito bite and a shark bite—people can put up with pain from a mosquito bite, but not a shark bite. Therefore, choose carefully the pain points you emphasize. To summarize, as you select relevant information for your message, consider all of the following options

Messenger As a messenger you need social capital, or respect and credibility (Graber’s second condition and part of Aristotle’s concept of ethos). You need to gain people’s trust—to connect with the audience and win their hearts. People gain the trust of others when they embrace goodness in a variety of ways: 1 Telling the truth. 2. Fulfilling their responsibilities; completing what they say they will do. 3. Making good decisions and doing high-quality work. 4. Working for the good of the team or organization, not for their own selfish interests. 5. Acting in a socially appropriate manner, and always keeping their emotions under control. For some audience members, our presidential candidates have multiple strikes against them even before they walk onto the debate stage! In spite of this baggage, during the debates they can help repair their damaged reputations by telling the truth, acting in a socially appropriate manner, keeping their emotions under control, and working for the good of the country—not for their own selfish interests. As a messenger, you also need good persuasion skills, Graber’s third condition. Of course, you must have well-planned, relevant information (the what), but you must also present your case in such a way that the information actually persuades (the how). Here are a few examples:

Audience Graber’s fourth condition for achieving persuasion states that the audience must be open to persuasion. When persuading in your own organization, first understand the mood of your audience regarding your proposal. Often, it might be best to present your ideas to individuals one on one. Then, after you know the feelings of individuals, meet with the larger group to achieve full buy-in. For Clinton and Trump, the large majority of the nationwide audience is not highly persuadable at this point in the campaign. Their minds are already made up (although each candidate needs to continue to reinforce that commitment). Therefore, in the remaining debates, candidates must concentrate on the persuadable portion of the audience. As you watch the remaining presidential debates, keep in mind the foregoing message, messenger, and audience elements and see how well Trump and Clinton perform. Further, begin to apply these guidelines and principles in your own persuasive presentations. See if they help you improve your own win-loss record. -Bill Baker References Graber, Doris. 2003. The Power of Communication: Managing Information in Public Organizations. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. |

AuthorsWe're Bill, Matt, and Vince, and we hope these posts will help you more effectively teach business and professional communication. If you like what you read, please consider teaching from our business and professional communication textbook. Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed