|

I find it helpful as a business communication instructor to take a step back every so often to look at the current trends in workplace communication. This helps me to keep my teaching relevant for my students. One thing that I consider when I look at workplace trends is how employers see communication skills. This blog post will go over a bit of what I found when I read the article Employer’s Perspectives on Workplace Communication Skills: The Meaning of Communication Skills, by Tina A. Coffelt and Dale Grauman of Iowa State University, and Frances L. M. Smith of Murray State University.

In their study, Coffelt and her coauthors looked at four modes of communication: written, oral, verbal, and electronic (WOVE). They held interviews with 22 participants who hire or supervise recent graduates. In interviews, they asked questions to assess what the phrase “communication skills” means to these employers. As you can imagine, a question like that yielded many different answers, but the researchers found themes despite the variation in answers. One particularly interesting take away from the article was about electronic communication. For instructors and researchers, electronic communication can mean many things. However, in the study, “employers considered electronic communication to be email.” Further, “email was overwhelmingly described as pervasive and the modus operandi.” The employers’ narrow focus on email as electronic communication was an eye opener for me. As instructors of both Millenials and Gen Z students, we know that email skills are still one of the most important areas we can help our students develop. I am often more excited about teaching my students about newer technology, but the article helped me remember that the fundamental way employees communicate at work (email) is not going away. For me, that does not mean new technology topics will go away but just that the fundamentals should come first. You can read their entire article here. And feel free to share your own thoughts and insights in the comments. How do you teach email? What email-related resources do you share with your students? To learn more about teaching students about email correspondence, check out Chapter 3 in our textbook on composing business messages as well as this post on using the PAST acronym to avoid email remorse. -Adam Walden Source: Business and Professional Communication Quarterly Image by Rawpixel

3 Comments

Three Essential Social Networking Skills for Business and Professional Communication Students5/31/2019 Staying current on the ever-changing features of social networking sites (SNS) can be daunting for anyone who teaches business or professional communication. Shifting focus from site features to student skills can help.

In a study led by Alexander J.A.M. van Duersen of the University of Twente, the researchers propose three groups of SNS skill for professional communicators: Communicating: The researchers assert that SNS communication skills involve both communicating so others can understand you, and listening so you can understand others. Specific communication skills include effectively using SNS for external and internal correspondence, writing understandable narratives, understanding others’ emotions over chat, and participating in forum discussions. Creating: Creation skills involve knowing how to create and publish professional SNS content for your organization. The researchers highlight skills of creating online media that communicate and align with your organization’s brand and values, and creating and publishing content in a way that enables and receives positive engagement from other users. Strategizing: Strategy skills focus on making decisions, which includes gathering and analyzing SNS information and then using that information to achieve organizational goals. Specific strategic skills include using SNS for gaining customers, increasing profitability, getting ahead of competition, and enhancing relationships with stakeholders. By focusing on the skills of communicating, creating, and strategizing, business and professional communication instructors can stay focused on what really matters: helping students gain skills that will transfer beyond the next site update. Read the entire article “Social Network Site Skills for Communication Professionals: Conceptualization, operationalization, and an Empirical Investigation” by Alexander J.A.M. van Deursen, Carla Verlage, and Ester van Laar to learn more about essential SNS skills you can teach your students. To learn other tips for teaching students about social media communication, take a look at Chapter 6 in our textbook Writing and Speaking for Business. -Matt Baker Source: IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication Image by Gerd Altmann —Matias, a retail store manager, must tell his employees that store hours will be extended one additional hour into the evening.

—James, a customer service manager, has to deny a customer’s request for a refund. —Heidi, a personnel manager, needs to document in an email why a subordinate is being put on probation. Each of these situations involves giving bad news, while still attempting to retain goodwill with the person receiving the news. Sooner or later, everyone in positions of responsibility has to give bad news, which is rarely a pleasant task. There’s no one right way that works in every situation, but here are a few tips that can help. Start by completing a CAPS planning process, ultimately selecting appropriate communication strategies. Context analysis: Identify the factors that make this bad-news message necessary. What is your current relationship with the person? Is it a positive, neutral, or negative relationship? What would you like your future relationship to be like? What is needed to move your relationship to the desired level? Is the message recipient inside or outside your organization? If inside, remember that you’ll have to work with this person in the future. Audience analysis: Look at the situation through their eyes. Try to comprehend how the bad news will affect them. Then sincerely try to minimize the negative effect of the bad news. Purpose: Clarify the purposes of your message—to inform, to persuade, and to strive to build, maintain, or strengthen trust. Decide on what you think would be the ideal outcome of your message. Strategy: Take steps to achieve the ideal outcome. Consider using the following four strategies—provide good reasoning, use an appropriate psychological approach, provide options as appropriate, and use appropriate wording 1. Provide good reasoning. Ideally, you want the readers of your negative messages to agree that you are justified in your reasoning. Therefore, be sure to have good reasons, whether financial, legal, ethical, or otherwise. Then clearly explain your reasoning in the most persuasive way possible. Example: “With more daylight during the summer evenings, more customers are shopping later, so we need to keep our stores open longer to meet their needs.” Regardless of your reasoning, people are still receiving bad news, which they won’t be happy about. But if you can convince them that you used solid reasoning in arriving at your decision, that will usually help soften the blow. You might not feel a need to cite all the reasons for your decisions, but make sure to include the reasons that are most persuasive. For instance, your main motive for terminating someone might be their negative attitude, but because negative attitude is so difficult to measure or quantify, you might just cite discuss their substandard customer service ratings as the reason for your decision. In your reasoning, include any benefits coming from your decision. Example: “This policy enables us to maintain our low prices, which provide benefits for you and all of our customers.” 2. Use an appropriate approach. If the impact on the audience is going to be minor, you can take a more direct approach. But if the impact will be major, an indirect approach will usually be best. With a direct approach, give the negative news at or near the beginning, followed by the reasons for the bad news. Example: “I’m sorry to have to deny your request for a replacement of your Columbia hiking shoes. These shoes come with a full-refund policy if the shoes are returned in like-new condition within 30 days. As we analyzed your purchase of these shoes, we found that the shoes were returned three months after purchase, not within the 30-day required refund period.” With an indirect approach, give the reasons for the bad news, followed by the bad news. Example: “Thanks for your request for a refund on your Columbia hiking shoes. These shoes come with a full-refund policy if the shoes are returned in like-new condition within 30 days. As we analyzed your purchase of these shoes, we found that the shoes were returned three months after purchase, not within the 30-day required refund period. Therefore, we are unable to give a refund.” To de-emphasize the bad news, you can also embed it in the middle of a paragraph. For example, begin the paragraph with the reasons for the bad news, followed by the bad news, followed by other information that softens the blow. Example: “These shoes come with a full-refund policy if the shoes are returned in like-new condition within 30 days. Because the shoes were returned after the 30-day required refund period, a full refund can’t be given. However, we are sending you a 30 percent coupon that you can use toward the purchase of another pair of shoes.” 3. Provide options. When giving bad news, try to find something positive to offer the person. Example: “I’ll be happy to give you time off to attend our monthly two-day customer-service training.” Also explain other actions the readers might take to minimize or reverse the negative situation, such as, “You can find additional online customer-service training to help improve your ratings.” 4. Choose appropriate words. As you give bad news, minimize the use of negative words, such as won’t, can’t, and didn’t. Instead, use more neutral or positive words. For example, instead of saying, “We can’t give you a refund,” you might say, “If the shoes had been returned within the 30-day period, we would have been able to grant your refund request.” Also, you can use passive-voice sentence construction, instead of active voice, in conveying the bad news. Don’t say, “Because of your 2.6 customer service rating, I can’t give you a ‘Satisfactory” review.” But rather say, “Because of your 2.6 customer service rating, a ‘Satisfactory’ review can’t be given.” The foregoing tips are proven methods for dealing with delivering bad news, whether in face-to-face situations or in writing. As you apply these methods, you’ll find that both your confidence and your effectiveness will increase. –Bill Baker Consider using “pyramid quizzes” for high-involvement learning. Pyramid quizzes progress from small to large—beginning with individual thinking, moving to small-group sharing, and concluding with entire-class discussion.

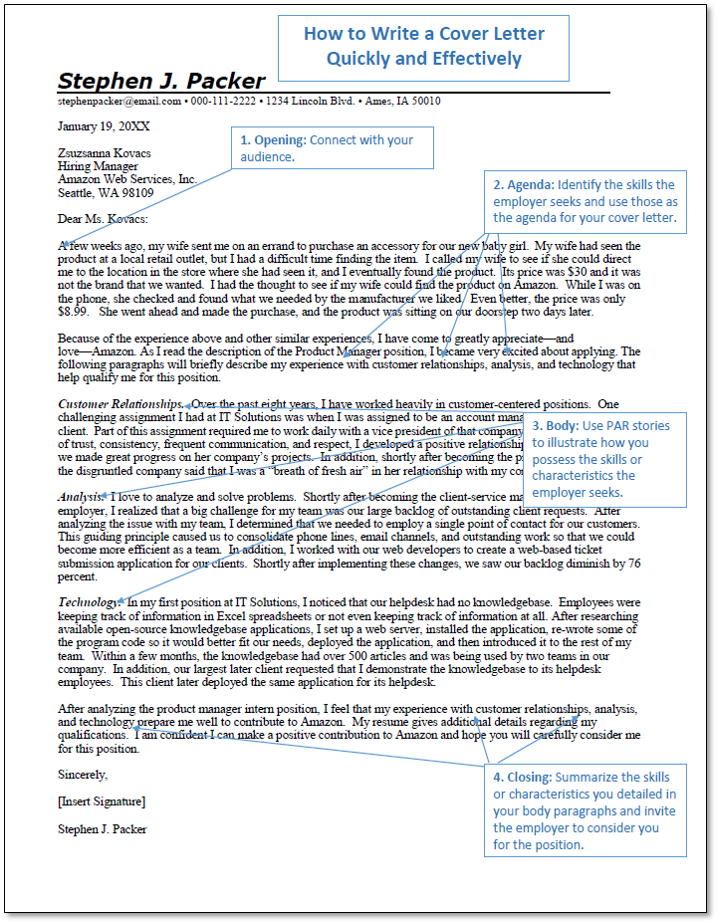

Pyramid quizzes are especially useful in learning grammar and sentence basics. For example, students complete a punctuation reading assignment (for an example, see pages 260–65). Then in the subsequent class, you administer the pyramid quiz as follows: Round 1. Each student completes a closed-book punctuation quiz (for an example, see pages 279–81). Round 2. In teams of three or four, students compare quiz answers. Then counseling together, and consulting the textbook as needed, they come to a consensus on the correct quiz answers. Round 3. Instructor gives the correct quiz answers, facilitates appropriate class discussion, and gives appropriate explanations to ensure learning. Try pyramid quizzes this semester. Both you and your students will enjoy this active-learning process. -Bill Baker If you’re having trouble writing a cover letter for employment, there are good reasons. Because a future job is on the line, cover letters are high-stakes communication. Usually, they’re written under a deadline (the closing date for a job opening), which makes the writing even more stressful. They also need to be personalized to each employer, and since most job seekers apply to multiple jobs, this translates into a lot of time. To overcome some of the stress and time of writing cover letters, I’ve created a template that enables me to write cover letters quickly and effectively. Following an OABC organizational structure, the template includes four parts. Opening: Connect with the hiring manager or company in some way. For example, mention a shared acquaintance, talk about how you’ve researched the company online and appreciate the values or mission of the company, detail what you’ve learned through an information interview with a current or past employee, or share a positive experience you’ve had with the company’s products. The goal is to show enthusiasm and to signal your sincere interest in the job. Agenda: Identify the skills or characteristics the employer seeks and that you possess. For help in this process, review our previous blog on preparing to communicate for jobs. Select two or three skills and use them for the agenda that forecasts your body paragraphs. Body: Relate a PAR story that illustrates each skill or characteristics you selected for your agenda. For help in this process, review our previous blog on PAR stories. Closing: Summarize your characteristics, and then invite the employer to consider you carefully for the position you’re applying for. To see all of these pieces put together, take a look at this example: I invite you to try out this template the next time you apply for a job. I think you’ll find that you can write cover letters more quickly and effectively as a result.

-Matt Baker |

AuthorsWe're Bill, Matt, and Vince, and we hope these posts will help you more effectively teach business and professional communication. If you like what you read, please consider teaching from our business and professional communication textbook. Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed