|

In one of our previous posts, we reviewed research about a way to assess whether students are considering their audience as they write; in this post, we review research about how students can enhance their consideration of their audience in their writing.

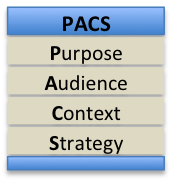

The Research This research is less recent than some of the studies we reviewed in other posts, but its conclusions are worth highlighting. Linda Carey, Linda Flower, John R. Hayes, Karen A. Scrivener, and Kristina Haas from Carnegie Mellon investigated how planning can affect writing quality. The researchers assigned a writing task to 7 novice writers and 5 expert writers. All 13 writers were to write to the same audience. As the writers completed their writing task, they were asked to speak their thoughts out loud so the researchers could capture their thought processes. Any thought processes that occurred before the writers wrote their first complete sentence were considered statements related to planning. The researchers analyzed the planning statements for content, for persuasion (purpose, audience, and organization), and for other goals. After the writers composed their documents, the quality of the documents were evaluated for audience adaptation, clarity of purpose, and structure. The results indicated that writers who planned for all three persuasive elements—purpose, audience, and organization—produced higher-quality documents. Further, writers of high-quality documents tended to plan more overall. Notably, these results transcended expertise, as three novice writers and three expert writers achieved the highest quality scores. The Implications The results indicate that if we can help our students plan more for purpose, audience, and organization, their writing will likely reflect greater attention to those persuasive elements. And in my experience, greater attention to those elements translates to higher-quality writing. To help my students plan for persuasive elements, I encourage them to analyze these elements using the PACS framework. In addition, when they organize information, I encourage them to not only categorize the information but also sequence the information so it meets the audience’s needs and is sensitive to the purpose of the document. Finally, I use case studies to build a rich situation so students have a purpose and audience to respond to. What strategies do you use to help your students plan for persuasive elements? We’d love to hear about them in the comments below. –Matt Baker Source: Center for the Study of Writing Image by DarkmoonArt

0 Comments

Business communication instructors agree that audience is a key consideration when composing business documents. But how do we know whether students are grasping what we're teaching them about the importance of audience? Reflections can be a good choice.

The Research In new research, Danica Schieber from Sam Houston State University and Vincent D. Robles from the University of North Texas assessed the use of reflections to gauge their students' awareness of audience. After responding to a case requiring them to write multiple business genres to varying audiences, students reflected on their audience awareness. The researchers uncovered three themes in the students reflections: -Identifying reader benefits and constraints -Considering reader values and priorities -Estimating one's own credibility The researchers found that students faced most difficulty delivering bad news to a customer and persuading a manager. Students found it difficult to "keep a positive tone while still giving bad news." When persuading a manager, students found it difficult to sound and feel credible, to avoid sounding "bossy," and to provide adequate detail. The Implications This study suggests that reflections can be a great tool for instructors to gauge their students' awareness of audience. Further, it suggests that different combinations of audiences (e.g, a customer versus a manager) and genres (e.g., persuasive versus bad news) can increase the difficulty of audience-focused assignments. If instructors want to provide their students with increasingly challenging practice, they might systematically adjust assignment audiences from an external customer to colleagues to a manager and adjust assignment genres from an informative message to a bad news message to a persuasive message. For additional information that can help students strategically consider their audience, consider using our PACS framework described in this post or in Chapter 2 of our textbook. You can also read the entire article “Using Reflections to Gauge Audience Awareness In Business and Professional Communication Courses” by Danica Schieber and Vincent D. Robles to learn more about using reflections to assess your students’ awareness of audience. If you have assignments or teaching strategies you use to help your students gain an awareness of audience, please share them in the comments below. -Matt Baker Source: Business and Professional Communication Quarterly Image by Free-Photos In your business communication courses, do you ever wonder how much emphasis you should be placing on writing emails? In “The Snowball of Emails We Deal With’: CCing in Multinational Companies,” Ifigeneia Machili of University of Macedonia, Greece; Jo Angouri of Warwick University, UK; and Nigel Harwood of University of Sheffield, UK confirm that email is the current most dominant business communication genre.

Emails are not, however, alone on center stage. They interweave with video conferences, phone calls, texts, webinars, and more. Also, they function interdependently with previous and subsequent emails, reports, face-to-face conversations, social media, local and remote meetings, and phone calls. Further, emails must be fluid and flexible as they develop credibility, build/maintain social and organizational relationships, and be sensitive to formality, politeness, credibility, accountability, self-projection, and multiple audiences. The Research In their analysis of email chains in an international organization, the researchers found that emails play a pivotal role in managing interpersonal relations and operational matters. Through discourse-based interviews, the researchers learned how employees strategically highlighted their professional achievements and owned or denied responsibility for decisions throughout the email chains. In addition to transmitting information, emails employed CCing (carbon copying) and formality to help (1) establish accountability, (2) contribute to decision-making, and (3) enable self-projection. The Implications The results validate the need for business communication instructors to include intensive email instruction. Students must realize that emails are not simple one-and-done messages, but rather critical communication exchanges that must be sensitive to a host of subtle contextual factors. Showing real-world email chains can help students become aware of the contextual twists and turns they will encounter on the job. Using scenarios and simulations, instructors can require students to write emails at different points in an email chain, developing appropriate strategy and content and deciding whom to CC. You can read their entire article here. Learn other tips about creating effective emails in Chapter 3 of our textbook Writing and Speaking for Business. -Bill Baker Source: Business and Professional Communication Quarterly Image by William Iven Recently I went to dinner with a former student who graduated 12 years ago. This student is now a successful attorney who writes numerous legal briefs and other documents that are read by judges and others in the legal profession. During the evening he described how he still uses writing and design principles I developed for my business communication classes: “I use OABC and HATS all the time in my writing, and they give me such a great advantage in writing for judges.” He also said, “I learned more in your writing class than in all the writing classes in law school.”

Obviously, I was happy to receive the compliment for my course, but his comments caused me to think about learning retention—what is it that enables students to remember and use writing principles learned in business communication courses? Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel (2014) have written a landmark book on this topic: Make it Stick—The Science of Successful Learning. Roediger and McDaniel are cognitive scientists whose careers have focused on learning and memory, and Make it Stick captures the results of years of their own learning. In this intriguing work, the authors conclude that people generally go about learning in the wrong way. For example, the idea that people learn better when they receive instruction in a manner consistent with their preferred learning style (e.g., auditory or visual) is not supported by research. Further, the idea is false that if we can make learning easier and faster, the learning will be better. In fact, learning that requires more mental work lasts longer. In addition to identifying what doesn’t work in learning, the authors also identify what does work. Three of their proven strategies likely helped my former student retain and use his classroom learning years after graduation. Mnemonics. First, use mnemonic devices. Mnemonics link a memorable name to a larger mass of information. In this case, OABC stands for opening, agenda, body, and closing. This acronym provides a proven pattern that can be used for many business writing situations. HATS refers to headings, art/graphics, typography, and spacing. After a basic message is crafted, students can add headings, appropriate graphics, typographic enhancements, and white space to make the message more visually appealing to the reader. The OABC and HATS acronyms provide easy ways for students to create clear, organized, and visually powerful messages. Integration. Second, integrate all the knowledge learned. All new learning has to connect with previously known information. OABC and HATS are taught early in the semester, and then they are integrated into subsequent assignments throughout the rest of semester. Thus, by the end of the semester, students have had experience applying OABC and HATS in a variety of contexts. Repetition. Third, all new learning requires a rewiring of the brain. Therefore, provide repeated application of new learning to create and reinforce the new wiring. Don’t assume that students have learned new material just because you have covered it once. Rather, continue to re-emphasize important material throughout the course. OABC and HATS are taught fairly early in the course, and students are required to apply the principles contained in these acronyms in all subsequent assignments. This repetition reinforces the learning, which improves the likelihood that students will continue to apply the learning later in their careers. The result is that my student now has these principles so deeply ingrained in his mind that they spontaneously come into his mind whenever he faces a writing project. Further, he not only knows how to use these principles but has a strong conviction of their value in his work. Today’s professional organizations spend millions of dollars each year on training, yet much of this training has little impact on participants’ subsequent business practices. In most cases, it is because real learning never takes place. Consider your own situation. Is there an opportunity for you to implement mnemonics, integration, repetition, and other Make It Stick learning tactics in your organization? If you are a trainer or teacher, I strongly recommend the reading of Make it Stick. Further, I suggest that you visit with a few of your former students (or current students at the end of a semester) and ask them to recall what they remember most from your instruction. If you’re not satisfied with their answers, take time to clearly identify what you want students to learn, and then reinforce that learning with principles of mnemonics, integration, and repetition. I welcome your comments. -Bill Baker You need to communicate with another person, but you’re a bit fuzzy about how you’re going to approach the situation and what you’re going to say. If only there were a clear pathway to help you prepare!

The following four-step PACS plan (Purpose, Audience, Context, Strategy) might be just the thing you need. Step 1. Purpose First, clearly identify your purpose. Usually, your purpose will be one or more of the following—to inform, to persuade, or to enhance a relationship. Within each of these generic purposes, state precisely what you want the outcome to be. Step 2. Audience Analysis With your purpose in mind, analyze your audience, remembering that your message might have both primary and secondary audiences. Consider the audiences’ demographic (e.g., profession, age, education, gender), psychographic (e.g., interests, beliefs, attitudes, preferences), and knowledge (e.g., general and technical) factors. Think about their wants and needs. Consider that there may be both driving and restraining forces battling for and against you in their minds. For instance, they might want to learn more about your product, but their busy schedule and their current financial constraints might be exerting a powerful negative force that is working against you. Step 3. Context Analysis In addition to analyzing the audience, analyze the context in which your communication will occur. First understand the unique attributes of the industry in which the audience works—whether banking, electronics, healthcare, or other. Learn also about major competitors in the industry. Second, consider relevant factors in the audience’s organization—its purpose, products, procedures, and problems. Finally, consider the unique situational factors—your previous interactions with the audience, the level of trust that exists between you and the audience, time pressures, technical challenges, and so forth. Step 4. Strategy Finally, based on the results of the first three PAC steps, develop a communication strategy. Creatively plan how you can navigate through the context and audience challenges to achieve your overall purpose. First, develop a channel strategy—considering the relative pros and cons of available channels, determine whether to make a phone call, write an email, send a text, or talk over lunch. Second, determine your psychological strategy—your overall approach (direct or indirect), your appeal (logical and/or emotional), and your tactic (positive and/or negative). For example, assume that your purpose is to get Sydney, a sales manager you met at a recent convention, to allow you to explain and demonstrate your sales-enhancement software—ultimately to convince her to buy your product. From your audience and context analysis, you know that her organization is lagging in the industry and needs to increase sales. However, you also realize that she doesn’t know much about your product or about you as a person. Therefore, you decide that your main strategy will be to capitalize on the pressure Sydney is feeling to increase sales. Using a relatively direct approach, you will demonstrate your product and provide client testimonials and research data that validate the effectiveness of your product. Using both positive and negative tactics, you will emphasize the benefits of adopting your product, as well as the hazards of delayed action. As needed, you will also present a side-by-side comparison of your product and that of your main competitor. But first, you’ll strengthen your relationship by making a phone call to invite Sydney to lunch where you can learn more about her needs. During lunch, you will propose the idea of an onsite product demonstration. You’re now ready to pick up your phone and make the call, knowing clearly your purpose, and understanding as much as possible your audience and the context of the interaction. PACS planning has helped you feel confident and prepared. The next time you need to communicate, I invite you to plan with PACS. Remember the old adage—if you fail to plan, you plan to fail! -Bill Baker |

AuthorsWe're Bill, Matt, and Vince, and we hope these posts will help you more effectively teach business and professional communication. If you like what you read, please consider teaching from our business and professional communication textbook. Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed